Thanksgiving day is over, but a weekend full of leftovers is ahead! While you’re trying to figure out what to do with all of that leftover turkey, why not learn a little about how that bulky bird was raised? Or, rather, how that bird would have been raised a couple of generations ago.

While commercially-produced turkeys today are Broad Breasted Whites, 70 years ago Bronze was the breed (and color) of choice. In fact, my grandfather started out raising Bronze turkeys, but both my father and my brother raise Broad Breasted White. Of course, some smaller operations today raise heritage turkeys, including the White Holland (an ancestor of today’s widely raised Broad Breasted White), Narragansett, and Bourbon Red.

Let’s say you want to be an old-fashioned turkey farmer. Well, there are few things you need to know: sanitation and disease prevention, equipment, how to care for baby turkeys, and how to feed them until market age.

Sanitation and Disease Prevention

Sanitation and disease prevention were just as important in the old days as it is today. The USDA Farmer’s Bulletin No. 1409: Turkey Raising, 1940, provides some guidelines and common practices regarding this issue. It was incredibly important that farms had some sort of sanitation system in place. These included making sure the range had clean soil, feeding birds from feeders that couldn’t be contaminated by their droppings, and always keeping the buildings sanitary. When it came to feed, sanitation of containers was especially important when milk was used (yes, turkeys used to be fed milk). Of utmost importance was keeping turkeys separate from chickens and any other poultry – diseases are easily spread from poultry species to poultry species (this includes pet birds)!

Swift’s Turkey Feeding and Management Guide, undated but from the pre-Broad Breasted White era, provides some additional guidelines. These include availability of fresh, clean water at all times, cleaning and disinfecting brooder houses before new poults arrive, regular disinfecting of equipment, and not allowing visitors to enter turkey buildings or walk on the range, as diseases are easily spread between flocks. These practices are generally still in place today.

Now that you know how to keep your birds healthy, you need to know what equipment is needed.

Equipment

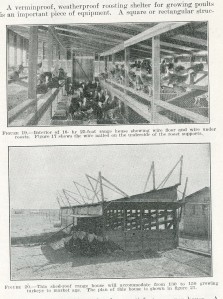

Swift’s Turkey Feeding and Management Guide recommends equipment to be used to raise 1,000 turkeys – a number that pales in comparison to today’s 10,000+ on turkey farms. Poults (the proper term for baby turkeys, not “chicks” like this guide calls them) were commonly raised both in brooder houses – and still are today, although the buildings are much larger – and on the range (outdoors).

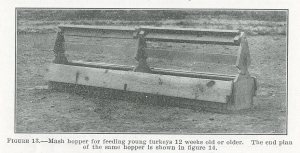

Equipment suggested in the guide include 4-foot long feeders, so that poults always have access to feed, 3-gallon poult-sized fountains for water, larger 6-foot long feeders for when the turkeys get a little bigger, 4 stoves designed for 500 poults each; these were used to keep the turkeys warm. Stoves are still used today, suspended in the air so they hover above the poults, like a low-hanging, warm roof. Brooder houses at the time were recommended to be 10×12 feet or so, with equal size sun porches for fresh air. For the range, 6-foot long feeders were recommended and 4-foot long watering troughs, rather than fountains. Also needed on range were shelters, fencing to keep turkeys contained, and shade.

With all of these set in place, you are now ready to add turkeys to your old-fashioned turkey farm!

New Poults

At this point the question is, how do you raise baby turkeys on a 1940s farm? The USDA Farmer’s Bulletin No. 1409: Turkey Raising tells us how to get started. First of all, the litter (stuff that’s put on the ground in turkey buildings) was supposed to be sand or gravel for the first two or three weeks, and then switched over to straw or hay. Today, sawdust is used throughout the turkeys’ lifespans.

Knowing when to start feeding your poults is also important on your 1940s turkey farm, since they have probably hatched on your farm. In 1940, leaving poults in a darkened incubator for 12-24 hours and feeding them as soon as they were moved to the brooder house was becoming the general practice. It also thought to be better than waiting for up to 72 hours, which was sometimes done.

I know you’re thinking, “Great, but when it comes time to feed them, what do I actually feed them?” Let’s take a look, shall we?

Feeding

The USDA Farmer’s Bulletin No. 1409: Turkey Raising comes to the rescue again, providing guidelines and recipes on feeding your turkeys. First and foremost, feed was to be available to turkeys at all times, from hatching to market.

The first feed poults were given was to be made up of green feed (finely chopped, tender) and dry starting mash (recipes to follow). Ground or crumbled hard-boiled eggs could be added to the mixture, and milk – “if not too high priced” – could be kept in front of them in easily cleaned containers, such as crockery, tin, wooden or granite.

For the first six to eight weeks, a well-balanced, all-mash ration was considered the simplest and most practical way to go. Commercial mashes were available, but they could be made at home as well. The following is one of two mashes that could be prepared, and the one the USDA recommended and fed without liquid milk:

Starting Mash No. 1:

- Ground yellow corn (17 parts by weight*),

- pulvarized whole oats (15),

- 50-55% protein meat scrap (12),

- Wheat bran (12),

- wheat middlings or shorts (12),

- dried milk (10),

- alfalfa leaf meal (10),

- 60% protein fish meal (10),

- cod-liver oil (1.5),

- fine sifted salt (.5)

* parts by weight add up to 100

After those six to eight weeks, up until market, the feed changed. It could included mash and whole grain or liquid milk and whole grain supplemented with insects and green feed. However, it was better to supply sufficient protein and minerals in the mash, as that would help with regular growth. The USDA guide provides four different growing mash recipes, but the main differences from the starting mash listed above include the omission of cod-liver oil, different amounts of each ingredient, and in some cases the addition of steamed bonemeal and ground oystershell or limestone.

With all this information (and much more thorough research conducted by yourself), you should be ready to run your own 1940s-era turkey farm! Or, maybe you just know a bit more about the history of turkey farming. That’s fine too.

More Information

For more information on raising turkeys and other poultry-related information – including how turkeys were prepared for market and how they were selected for breeding, see the Iowa Poultry Association Records, MS 67. We also have a book on the farm struggles of one man in the 1930s, including entries on turkey farming: Years of Struggle: The Farm Diary of Elmer G. Powers. Want to know how your turkey is raised today? Read this blog post (full disclosure: written by my sister-in-law) that provides a farmer’s perspective. The Iowa Turkey Federation is also a great resource – plus, they have lots of turkey recipes on their website, in case you haven’t figured out how to deal with all those leftovers yet.